WAR DIARIES: THROUGH THEIR EYES

We have been fortunate enough to have been donated diaries or memoirs by some of HMAS Castlemaine's crew— William Palamountain, William Hazeldene, Trevor McGarvey and Bruce Dyker. They offer us a unique opportunity to see what life was like through the eyes of those who lived and worked aboard Castlemaine during the war. (All documents are copyright © Maritime Trust of Australia Inc.)

1. Wartime Diary of William Palamountain

William John (Bill) Palamountain was born on 22 June 1923 at Mount Gambier, SA, and died on 23 October 2004. He served in the Radar crew on Castlemaine from 30 July 1942 to 30 September 1943, although the diary ends in July 1943. The document was transcribed by the ship's Archivist, Bob Pearson. Read the full transcript here: Diary of Bill Palamountain, 1942-1943.

2. Wartime Diary of William Hazeldene

William (Bill) Hazeldene was born on 30 June 1900 at Wolverhampton, UK, and died on 30 October 2001. He served on HMAS Castlemaine from 18 June 1942 to 15 June 1943, and HMAS Ararat from September 1943 to May 1944. The diary covers William Hazeldene's time on both ships. He was an Engine Room Artificer, a senior maintainer and operator of all the warship mechanical plant. The document was donated to the ship by the Queenscliffe Maritime Museum, and scanned and transcribed by Bob Pearson. Click sample images below for large versions and read the full transcript here: Diary of William Hazeldene, 1942-1944.

3. Memoir of Trevor McGarvey

Trevor Morris McGarvey was born on 12 February 1921 at Woollarah NSW, and died on 28 May 2012, 67 years to the day he joined Castlemaine. In his later life Trevor wrote his memoirs, kindly supplied to Castlemaine by his son David McGarvey.

Trevor's experiences are fascinating, because he served on a wide variety of HMAS ships, including a ferry, an ocean-going tug, two corvettes and a destroyer. He started out as an ordinary seaman and ended the war as an officer. His time on Castlemaine covers the latter stages of the war, describing the ship's life in a survey fleet off the north-west of Australia, and during the extraordinary period of the liberation of Hong Kong.

Trevor McGarvey: Memories4. Wartime Diaries of Bruce Dyker

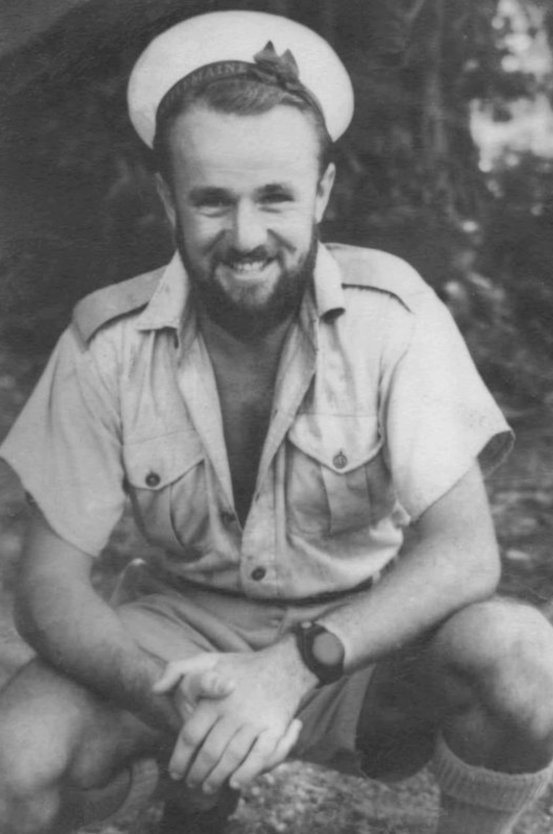

Bruce Sydney Dyker was born on 4 July 1920 at Richmond, Victoria, and died on 19 February 2007. Before the war he was a telegraphist, a trained morse code operator, who worked for the Post Office. He and Margaret were married in May 1942, just a few months before he joined Castlemaine, aged 22, and he wrote about her often — her letters were the high point of every arrival at a port.

Bruce served on Castlemaine from 18 June 1942 to 24 August 1944, then on HMAS Swan from 25 September 1944 to October 1945. He wrote eight detailed notebooks about his wartime life, full of gentle wit and keen observation, which are an extraordinary record of the times.

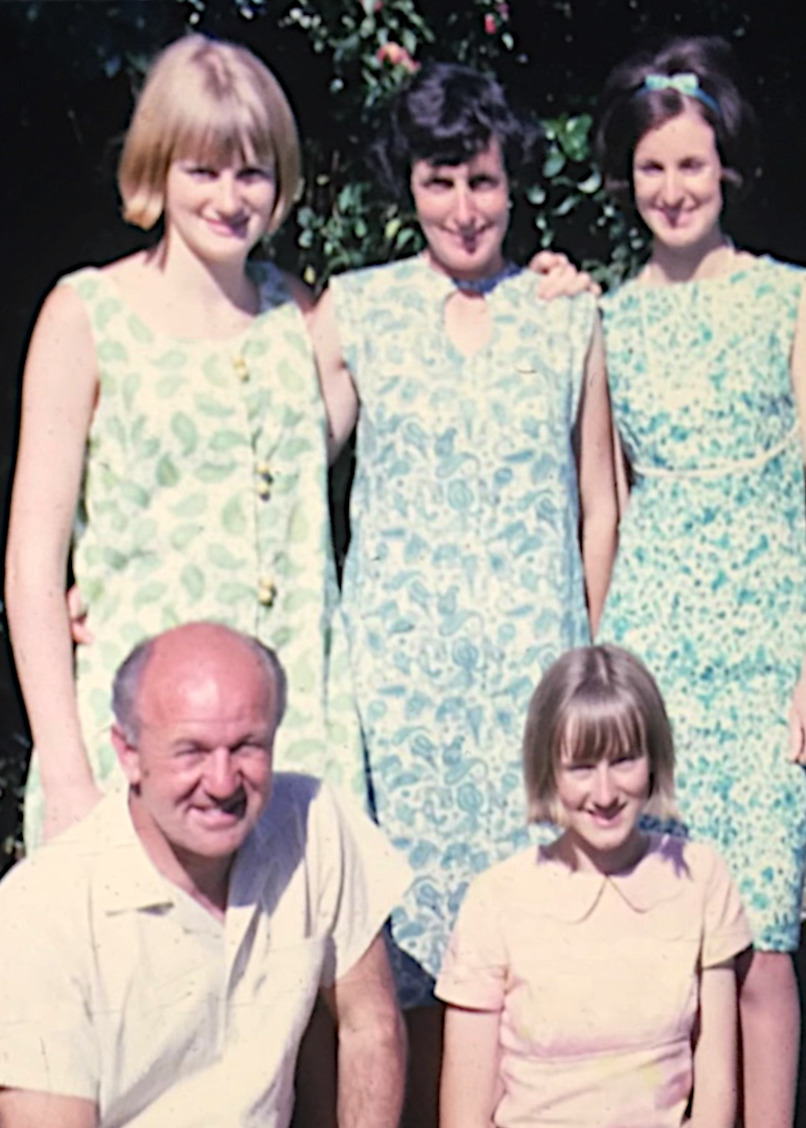

The Maritime Trust of Australia is extremely grateful to Bruce's family for the donation of the notebooks. The difficult job of transcribing them was organised by Bruce's niece, Verity Byth, in 2015. It required a team effort because only his daughters Christine, Roslyn and Geraldine were able to read the tiny handwriting and edit each other’s transcriptions. (Please be aware that the diaries contain offensive racial epithets that were common to this period.)

For more background, please see:- Margaret Dyker's reminiscences about the sometimes difficult post-war times for their young family.

- Kylie Lind's 1990 VCE assignment with information on Bruce's service and some of his photographs.

- The book HMAS Castlemaine – The Corvette that Came Home with more detail about life aboard Bruce's ship.

On corvettes there were at least 100 men living in areas no larger than a couple of lounge rooms … These diaries don’t always show the fear, the bravado, the loneliness, the intensive hatred, the concentration necessary to live just day by day, or even the intense physical effort required to keep up with the long hours and hard work, or the discipline necessary to cope mentally day after day.

Book 1 – 26 Aug 1942 to 7 Nov 1942

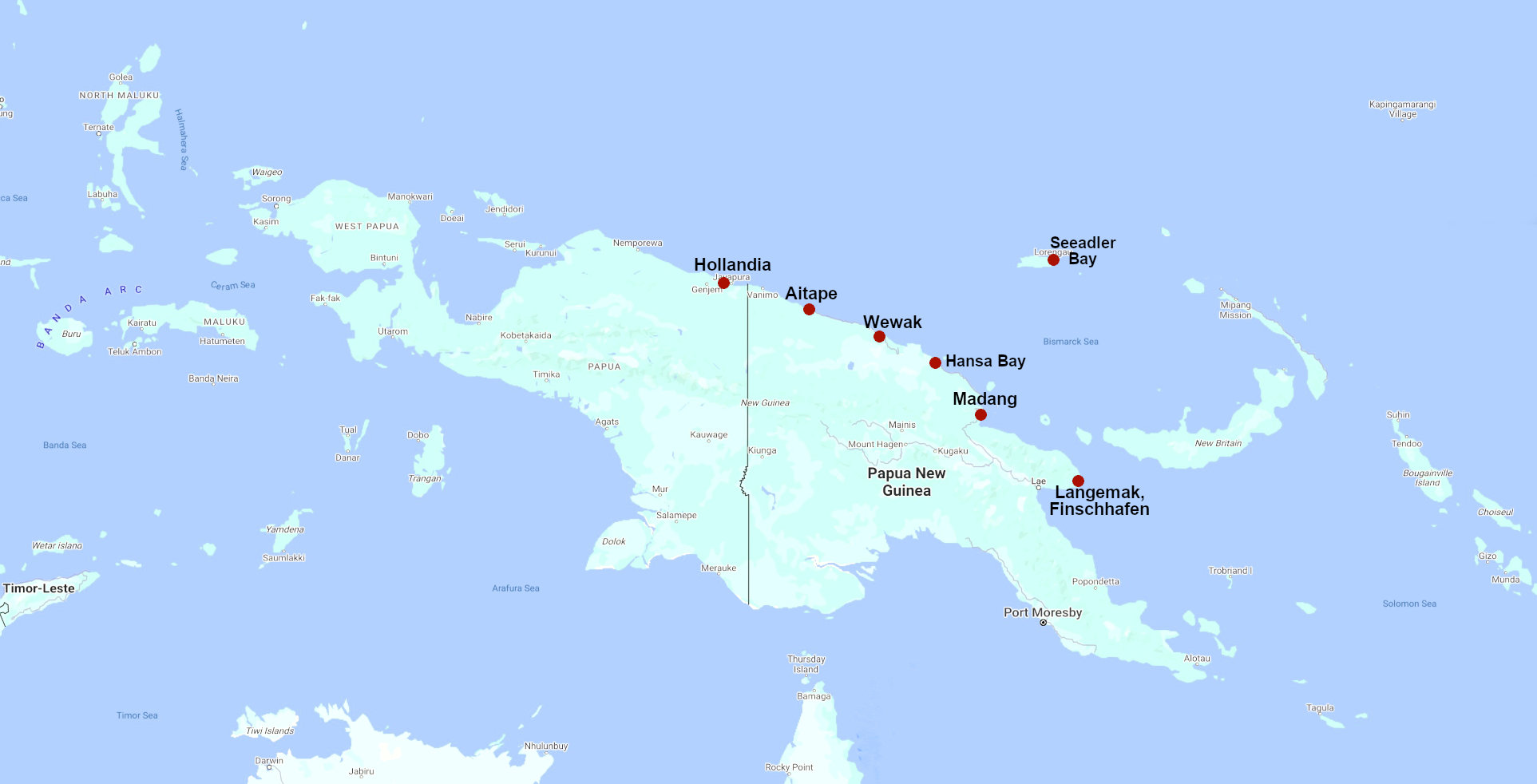

Bruce joined HMAS Castlemaine in Sydney on 26 August 1942. The ship left for Townsville on 31 August, then spent the next month escorting convoys between Townsville and Port Moresby, and on 12 September rescued two downed American pilots. On 30 September Castlemaine left Port Moresby, stopped at Thursday Island (at the tip of Queensland), and arrived at Darwin on 5 October.

Bruce worked tirelessly with the other radio operators on cleaning and maintaining their wireless equipment, trying to find spare parts and scrounging badly-needed items such as insulators and batteries. Castlemaine escorted several convoys between Darwin and Thursday Island, then on 6 November left for Timor on a dangerous mission to rescue Australian commandos and Portugese refugees.

Book 2 – 8 Nov 1942 to 16 Mar 1943

On 8 November 1942, Castlemaine returned to Darwin from Timor. The ship escorted convoys around Darwin, then on 29 November returned to Timor with the small ship Kuru and the corvette Armidale to rescue more soldiers and refugees. Bruce's good friend Arthur Ainsworth was a telegraphist on Kuru. During this mission all ships were attacked by enemy aircraft, and Bruce was very concerned about his friend's safety. Armidale was tragically sunk, and the few survivors were brought back to Darwin during the first week of December. During January and February 1943, Castlemaine escorted a number of convoys in Northern Territory waters and back and forth to Thursday Island, then in March began carrying supplies to bases and mission stations in the Territory and north-western Australia.

Book 3 – 17 Mar 1943 to 18 Jul 1943

While carrying supplies to missions, Castlemaine ran aground on 20 March 1943. From April to early July, Castlemaine returned to escorting convoys back and forth between Darwin and Thursday Island. On 7 July the ship left Thursday Island for Sydney, reaching there on 19 July 1943.

Book 4 – 28 Nov 1943 to 28 Jun 1944

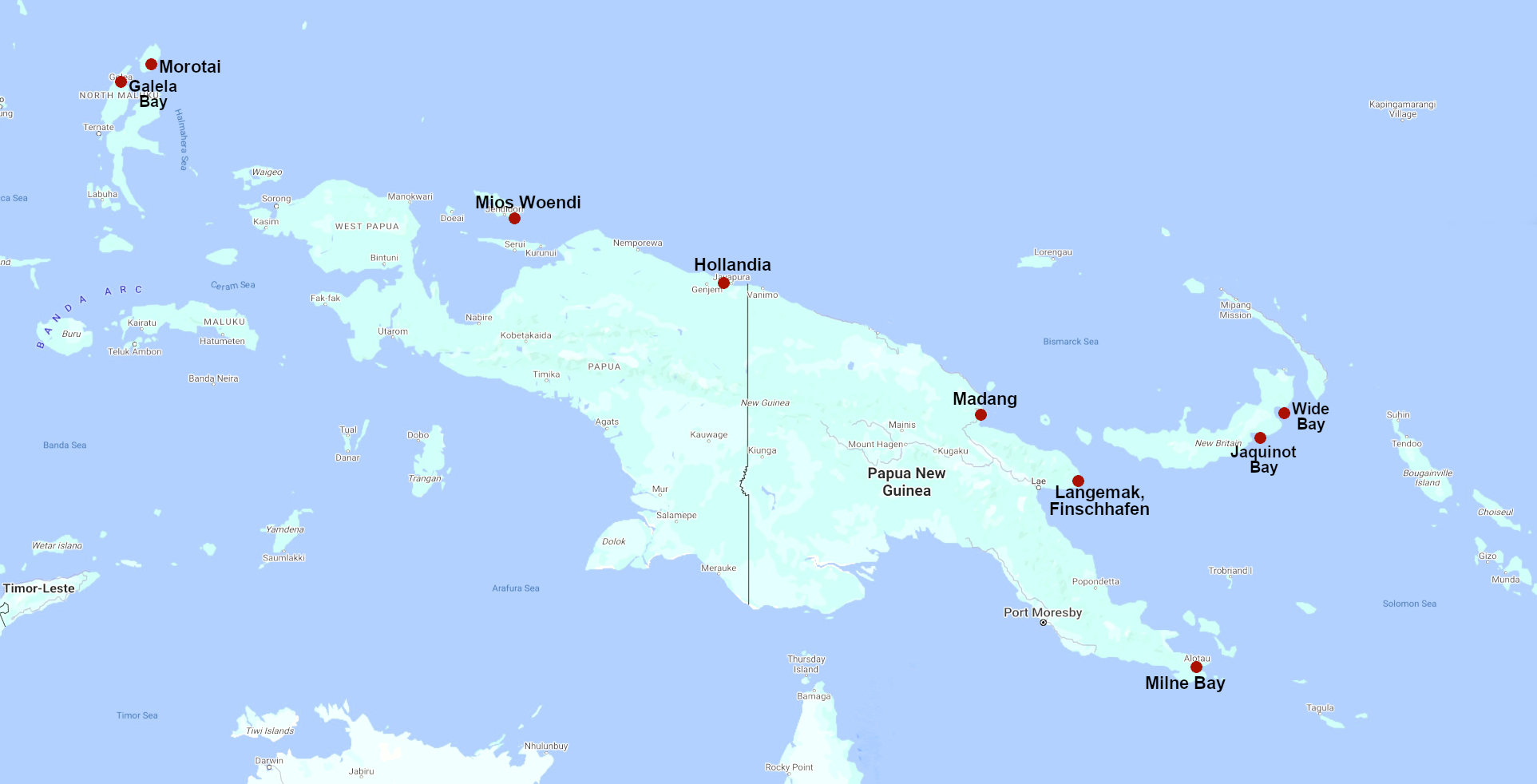

Castlemaine left Sydney for Townsville on 28 November 1943. It escorted convoys between Townsville, Cairns and Milne Bay in Papua, helping to free a number of ships that ran onto reefs on 19 December. On 24 December Bruce became ill and was admitted to hospital, then on 6 January 1944 was sent to another hospital in Brisbane to recuperate. On 25 January he boarded an American landing craft for the passage back to Milne Bay, reaching there on 3 February. He had to wait until Castlemaine arrived, and finally rejoined the ship on 25 February. In March Castlemaine escorted a number of convoys between Milne Bay and Cairns, then from April to June transported troops and supplies between Papua, New Guinea, New Britain and Manus Island. On 11 June Castlemaine left Papua for a refit in Adelaide, and Bruce took leave in Melbourne.

Book 5 – 25 Jul 1944 to 21 Oct 1944

On 25 July 1944, Bruce rejoined Castlemaine in Adelaide. The ship sailed to Fremantle on 7 August - where he had the welcome news from Margaret that he would become a father the following March. Castlemaine sailed along the Western Australian coast, reaching Onslow on 15 August and Darwin on 20 August. There Bruce was told he was being transfered to another ship, HMAS Swan, which was in Sydney.

He left Castlemaine on 24 August 1944, travelled overland via truck convoys to Larrimah and several staging camps, and reached Alice Springs on 7 September. He boarded a train there on 10 September, arriving in Adelaide on 12th September and Melbourne on 16th, where he had two day's leave with Margaret. He got to Sydney by train on 19th, and on 25 September joined HMAS Swan. Swan had just returned to Sydney from Papua, so Bruce was able to take a week's leave, and returned to Victoria to spend time with Margaret, now living in country Horsham.

Book 5 (continued) – 21 Oct 1944 to 27 Jan 1945

Swan left Sydney for New Guinea on 21 October, to provide escort, patrol and bombardment support in New Britain. Bruce thought Swan seemed a 'happy ship.' She was a Grimsby Class sloop, a larger ship than Castlemaine. Bruce said she 'had four times the firepower of a corvette.'

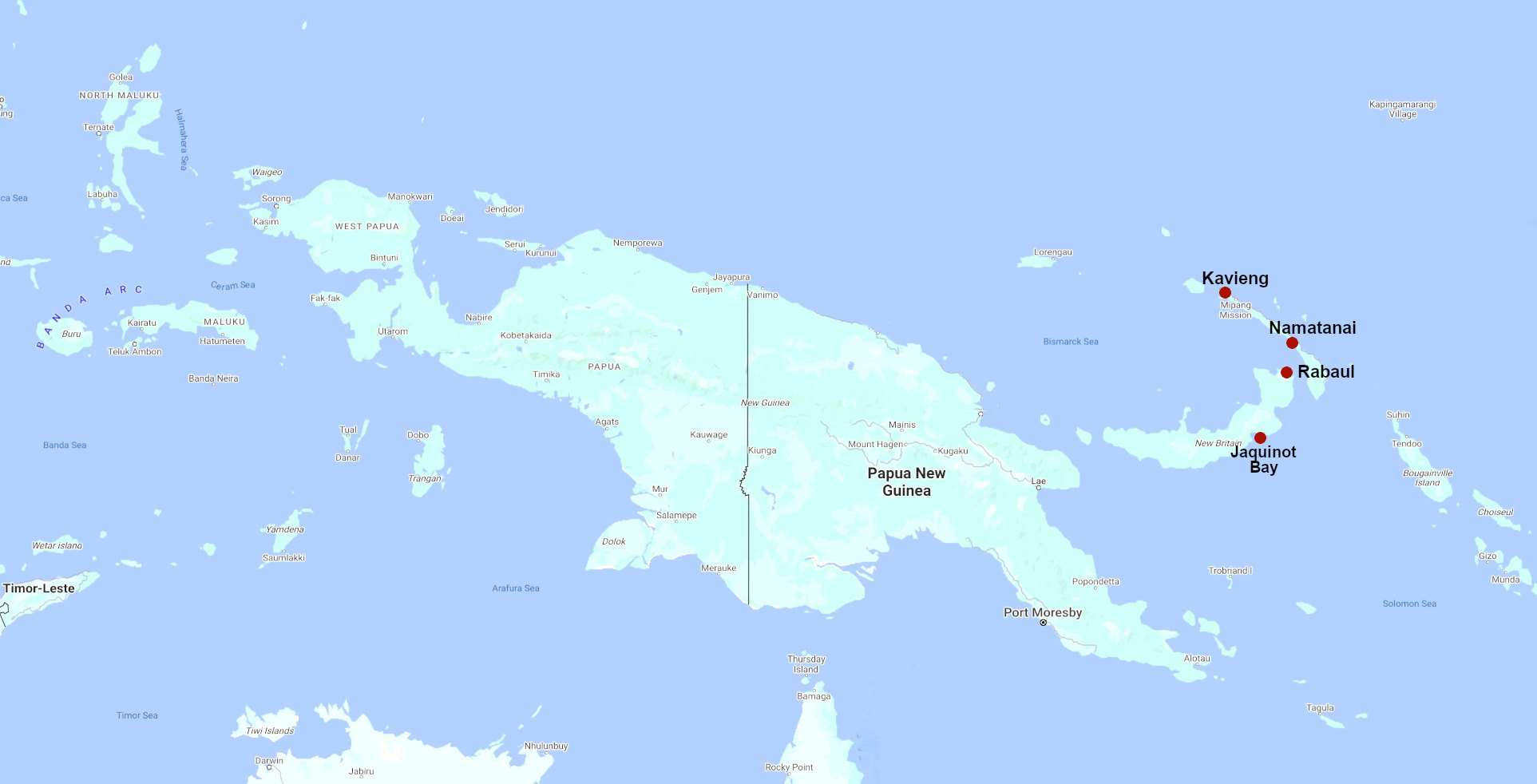

On 4 November 1944, Swan took part in Operation Battleaxe, providing support and landing soldiers for the Australian landing at Jacquinot Bay, an operation to establish a logistics base on New Britain to support operations near the major Japanese garrison at Rabaul. After bombarding enemy positions ashore at nearby Wide Bay, Swan returned to Madang, to the unwelcome news that the ship was to become a base ship at Mios Woendi, an island to the north of what was then Dutch New Guinea.

On 23 November they stopped at Hollandia, among 200 ships already anchored. On 26 November Swan arrived at Mios Woendi, which Bruce jokingly labelled 'Miss Windi.' In November 1943 and January 1944, the ship sailed several times to the Molucca Islands, about 800 km north-east, to bombard enemy positions. At Morotai, Bruce recorded he was working in 103F degrees heat all afternoon in the wireless cabin.

Book 6 – 5 Feb 1945 to 26 Apr 1945

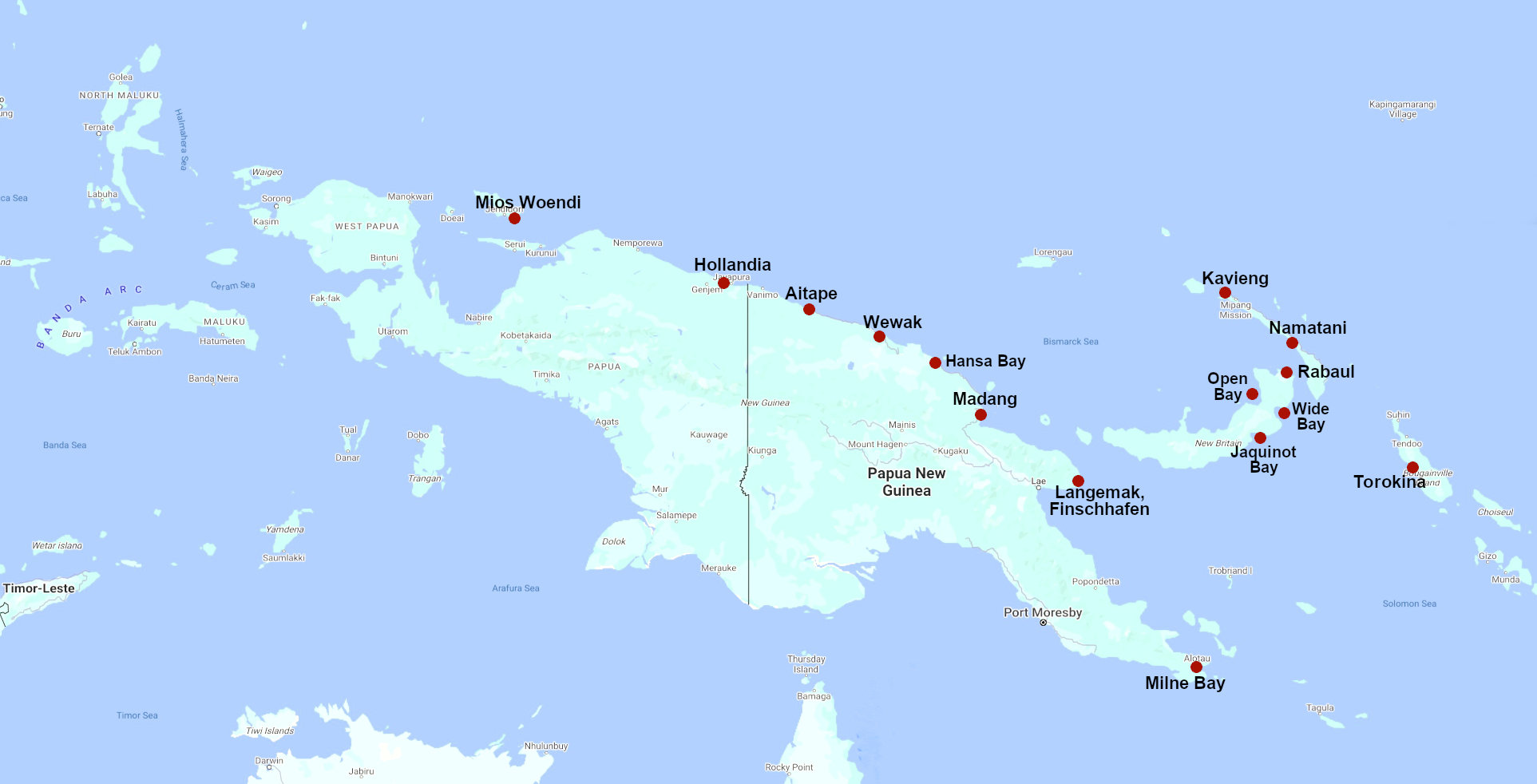

The shore base staff transfered to HMAS Platypus in February 1944, but to his relief Bruce was not sent with them. He met old friends from Castlemaine, which he affectionally called 'Castlebluper.' Swan sailed back to New Guinea, then Bougainville, then returned to the northern coast of New Guinea, transporting soldiers and bombarding enemy bases. Swan sailed to New Britain in March, shelling fortifications at Open Bay and around Rabaul. On 12 March the ship rescued two American sailors drifting in a motor-boat. Bruce appreciated Swan – during a heavy storm he wrote 'I reckon this ship is a good sea-ship tho’. We’d be taking a hiding in a corvette now.'

Bruce was delighted to discover his daughter Christine had been born on 1 April, then the rest of that month followed with passages between northern New Guinea and New Britain. Swan's CO, Capt WJ Dovers, was appointed head of Wewak Force, which also included the corvettes Colac, Ipswich and Deloraine.

Book 7 – 27 Apr 1945 to 17 Jun 1945

On 9 May Bruce heard the welcome news of Germany's collapse in Europe, and Swan began an intense period of bombardment around the Wewak area in support of Australian Army advances. Wewak was captured and Swan was the first Allied ship to anchor in its harbour since the start of the war. Swan returned to Madang, where Bruce turned 25 on 4 June 1944. The corvette Colac had been damaged at Bougainville, with two stokers killed, so Swan was assigned to tow Colac to Sydney. They left on 7 June and arrived in Sydney on 18 June. Bruce took leave while the ship underwent a major refit.

Book 8 – 6 Sep 1945 to 5 Oct 1945

Japan capitulated on 15 August 1945, but Swan still had work to do, and Bruce regretfully noted they left Brisbane on 6 September, heading north once more. They arrived at Rabaul in 12 September, where Bruce wrote: 'It seems strange to see the Japs driving about or working at their gardens, after fighting them for so long.' On 18 September Lt Gen Eather, General Officer Commanding the Australian 11th Division, came aboard, and on 19 Sep Swan arrived at Namatanai in New Ireland to accept the official surrender of Japanese forces. Later that day they sailed to Fangelawa, near Kavieng, for another surrender ceremony. Finally, on 7 October 1945, Swan left for Brisbane, and the entries end. Bruce left service as a Leading Wireless Operator, two ranks above his original position. In 1980 he added the moving recollections below to Book 8.

At the age of 60, Bruce Dyker recalled:

“Looking back in retrospect and re-reading these diaries, it would almost seem that life then consisted of swimming and general sport, mixed with bouts of sea time. However the reality was different - sport was encouraged in leisure times to occupy the mind. Many who didn’t participate in sport became depressed and had to be sent south for treatment.There were long hours of repetitive boredom at sea in cramped conditions with most of the time food being uninteresting or tinned. Working in watches sometimes meant 4 hours on duty 4-6 hours off, but when off duty there were other required duties to perform.

During action or alarms, or even practices, one could be off duty but required for action station duty for hours, night and day. Then when action was over go back on watch keeping duties in the radio cabin (about the size of a bathroom). So work was mostly 12 -16 hours a day and in some cases I can remember never laying down for more than an hour at a time for days.

During alert “Red Signals” although an air raid or gun attack might not touch the ship, there was the fear of not knowing - or the fear that friends on other ships or ashore might be killed.

During landings, or convoys, or shoots, where there was a danger of attack I carried a body belt with my money, my 1⁄2 a penny, photos of the family etc always around my waist, because the possibility of ship being hit and sinking was always with us.

References to going ashore didn’t mean a pleasant ride to a jetty always. Skippers of ships realised that a break from the confinement of a ship's wassdecks? [messdecks] was good for morale. So in most cases we found our own way ashore, sometimes even swimming and floating our clothes on a raft. Each crew member then had something to talk about on his return.

The physical effort of escorting slow supply ships at such slow speeds in rough weather could easily jade the nerves and cause tensions among the crew which could lead to trouble in such cramped conditions.

Night after night and day after day of holding on to everything while you walked or ate was a physically and mentally strain.

On corvettes there were at least 100 men living in areas no larger than a couple of lounge rooms. It therefore became necessary to work together to build up a common pride of the ship and its achievements. In this way we became like a family each interested in the achievements of others.Overriding what appears perhaps casual, and at times even pleasant, was the separation from home and family and the constant doubt whether we might never see them again.

I have sat for hours in a small (not air conditioned in those days) hot humid wireless office with headphones on, and static caused by bad reception conditions nearly deafening me, while we have been engaged in some sort of dangerous situations, and have not known what was happening outside - whether we were in danger or safe. It wasn’t always that way, of course - but it must be remembered that we were all in our early 20’s - at an impressionable age.

In my case this spread over 4 years. On our return to normal life we felt that people didn’t understand what had happened - things in normal life hadn’t changed much but we had. After the war most of us had a restlessness that took time to lose. We missed mateship, a common language (even the swearing), and the disciplined routine.

We felt that civvies thought that all of a sudden we should forget 4 years of change in our lives (not bought on by ourselves). Possibly they were right - the past, once over, is only a memory or emotion, but it took us a long time to learn that, and in the process many suffered, because of the mental conflicts.

These diaries don’t always show the fear, the bravado, the loneliness, the intensive hatred, the concentration necessary to live just day by day, or even the intense physical effort required to keep up with the long hours and hard work, or the discipline necessary to cope mentally day after day.

But that's a long while ago - and perhaps means nothing except to me and others like me and perhaps for that reason isn't worth the comments.”

BD 1980