RATINGS' LIVES

Living conditions for the ratings, like their duties, were dictated by their rank. Whilst the captain and officers had private accommodation, the ratings had little privacy and slept in either the forward mess decks or outside on the external decking. The only exception to this was the Chief and Petty Officers, whose messes were directly below the forecastle mess, adjacent to the victualling store and directly above the ship’s magazine.

Life aboard each corvette was carefully organised to ensure the crew was ready for action, living in such a small space was tolerable and that each man pulled his weight. The essence of this organised arrangement was the watch system. This ensured that a part of the crew was on duty at any given moment when at sea.

There were five four-hour watches in a day with two-hour 'dog watches' between 1600 and 2000. This allowed rotation of the system so that men were not in the same watch each day. Each seaman was required to undertake all the duties of the watch such as lookout, helmsman (steering on the bridge) or manning one of the guns as well as having an 'action station' which was determined by his specialisation.

Every watch included enough seamen to handle the 4 inch gun, lookouts, a helmsman, radar and ASDIC operator, signallers and messengers. ASDIC and radar sets were operated by two men per set per watch. They operated for thirty minutes then handed over to the other operator, to prevent fatigue.

Several different types of lookout might be posted, according to the conditions. Far lookouts were posted in good visibility, including one in the crow’s nest. They scanned on and above the horizon. Near lookouts were posted on the bridge and they kept the horizon at the top of their scanning field. In bad visibility, fog lookouts were posted as far forward as possible to give warning of collision. Lookouts worked one hour periods, then were rested or allocated other duties to prevent eye strain.

Stokers on watch were stationed in the engine or boiler rooms or allocated to auxiliary machinery such as heating, electrical and steering equipment. The engineering personnel in the engine and boiler rooms were required to conduct a continual inspection of all machinery and equipment and make an hourly note of the operational pressures and temperatures in the log. Any repair required to equipment would be undertaken immediately, even if this meant mustering more men to assist with the work.

Food

Occasionally the menu included fresh fish caught by line or stunned by the detonation of a depth charge. There were three meals per day plus a substantial afternoon tea. Given the privations of the Great Depression of the 1930’s many crewmen believed they were relatively well fed.

Unlike the Royal Navy, the Royal Australian Navy did not provide a daily rum or tobacco issue to crewmen. Men could supplement their rations by purchasing items such as cigarettes, sweets, biscuits and cordial from the ship’s canteen. In the latter years of the war an occasional issue of beer was made to crews.

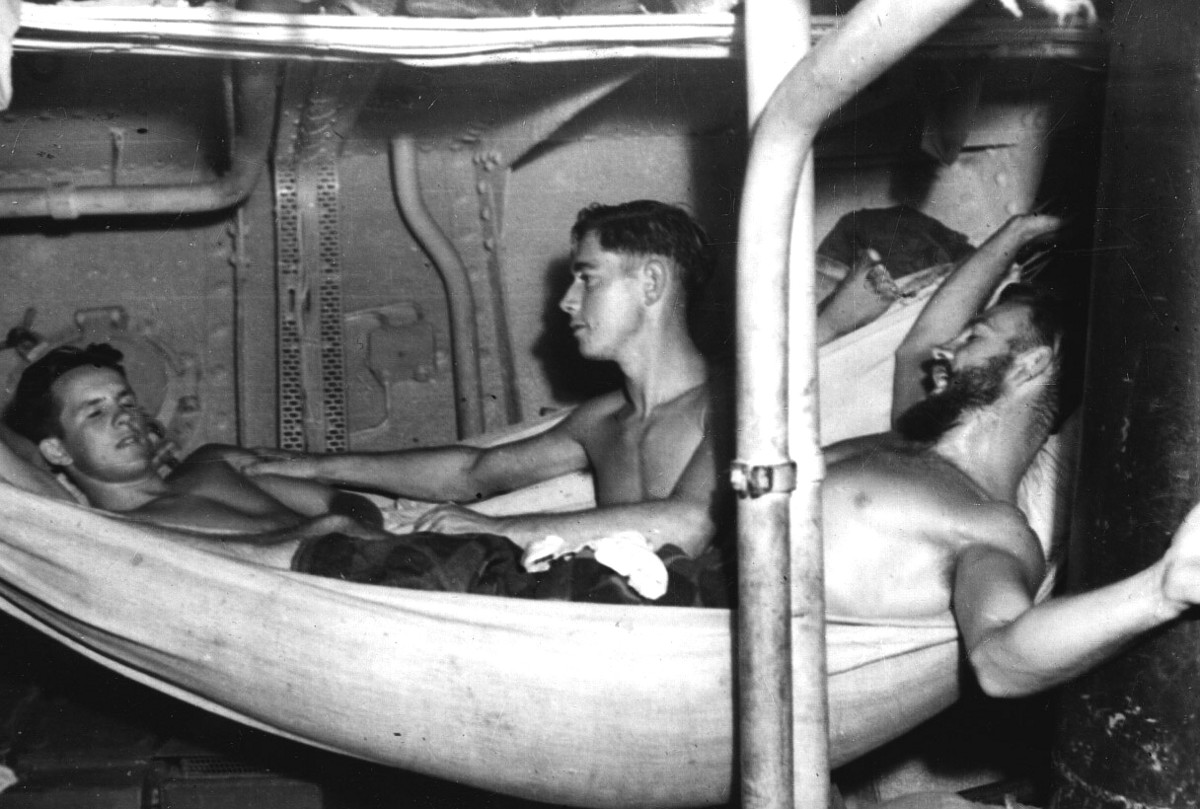

Bedding

Each sailor was issued with a hammock, mattress and a blanket. The messes and under-deck were fitted with hooks from which to sling hammocks and bins for storage when lashed up.

In reality, the men slept wherever they could find comfort. In the tropics, men would sleep on the deck in their hammocks or on mattresses slung or laid across areas and fittings which offered protection from the elements and which were out of the way for those men on duty.

A favoured area was near the funnel beside the vegetable locker. Aside from escaping the heat, many men who didn't smoke preferred to be away from the enclosed living quarters which were constantly filled with the haze of smoke. A major benefit of the hammock was that as it swung, a sleeping crewman was not jolted as the ship tossed about, with the ship seemingly moving around him, thus giving a more gentle night’s sleep.

Clothes

Upon signing up for service, every man was issued with two of most clothing items by the kit master. Aboard larger vessels the sailors could buy more gear but on smaller ships like the corvettes it was up to the sailors to make anything else they wanted or visit a clothing store (slops) ashore or on a larger naval vessel.

Hats were to be worn at all times, though the men had a fair amount of choice in what type they wore. Many sailors swore by army issue slouch hat which offered greater sun protection though others preferred the typical sailor cap with the ship's name along the tally ribbon.

Whereas the Navy employed a laundry washer drawn from the locals at visited ports for larger vessels, on smaller ships like HMAS Castlemaine it was left to enterprising crew members. Stokers in particular, due their work on boilers and being stationed in hot areas were able to easily wash and dry their own and others' clothing.

Water

Water for drinking, cooking and washing was carried in tanks situated in the hull of the ship. From these tanks it was pumped to a gravity tank on the main deck and fed into the galley and washplaces throughout the ship. This task took about thirty minutes and was carried out on each watch. Fresh water was distilled onboard from the surrounding seawater by a desalinator (evaporator) located in the engine room.

The sea water was boiled by steam from the boilers, condensed into fresh water and pumped into storage tanks. The evaporators also provided water for the boilers and because of their limited output, strict economy in the use of fresh water was observed onboard. The corvettes had two washrooms for the crew, one each for chief petty officers and petty officers and a separate washroom for the officers. The heads (toilets) used sea water for flushing.